Inside the cabinet of curiosities: V&A Storehouse East

The V&A East Storehouse was an incredibly exciting, innovative, and surprisingly moving experience that made me fall in love with museums all over again.

the museum of the future?

An unprecedented approach to curation for the public- much more than a window into the collection, this is total immersion.

Our studio team at D4R recently took time out of the office for an exploration and immersion day in London that included a visit to the newly opened V&A Storehouse East. I have been wanting to visit the V&A Storehouse since I heard about its planned opening back in 2020 and whilst I was aware it would be a fantastic opportunity to invigorate the team creatively, I was surprised by how many questions the experience posed to us regarding our interpretation of art, culture, and the purpose of preservation.

Widening gaps in education, social freedom, and mobility mean many in society are sceptical, cynical even, about traditional institutions such as museums and galleries.

A cost-of-living and climate crisis, and an age of attention deficit, has left many questioning whether these repositories of inaccessible, sometimes problematic, treasures truly serve today’s public.

The newly opened V&A Storehouse East responds to these questions by redefining the role of cultural institution and curatorial gate-keep; revealing the secrets and complexity of behind the closed doors, and in doing so humanising the people and processes that preserve our cultural heritage. The ground-breaking site presents an astonishing number of items up close and in reach; giving agency to the public- to explore, to engage, and to draw their own parallels and connections with our art and material culture.

Opening the doors; putting cultural heritage in context.

Unprecedented access to a designer’s dream sourcebook.

The museums of my remembered youth were about barriers- their glazed partitions defining the present from the past and only sharing the tip of an iceberg of wonders. It’s no surprise that the public have tended to feel distanced, and even worse- uninspired. This is why I find the Storehouse such an exciting space; in exposing otherwise hidden objects and the processes and work behind them with transparency, visitors are better able to understand their importance; finding their own interpretation and ‘moment’ of connection by having the context made visible and tangible.

In an interview with Frieze Tim Reeve, V&A’s Deputy Director highlighted the importance of this ambition to the V&A- ‘our collection is distinct. It’s like a sourcebook that is meant to be accessible to the public and to inspire creative practice… The more you open up the collection- the more you make it physically and intellectually transparent- the better’.

This ambition to open the collection with transparency is perfectly served by the architecture of the Storehouse building. Designed by the New York studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro- visionaries who transformed a disused railway into the High Line, reshaping how millions experience art, landscape, and city- the building is itself exemplifies this transparency of access and encounter.

It was wonderful to experience the visitor’s journey turned inside out. Instead of retreating from public into private, the Storehouse flips convention, placing the galleries at the centre of the building, surrounded by concentric rings of increasingly concealed deep storage. The layout offers self-guided access, the central core and radiating ‘arms’ are carved out of the dense storage racking and the glass balustrades and grid mesh flooring give the impression of being immersed in the collection, invited to explore, with unexpected wonders and surprising adjacencies at every turn.

{Image Credit: Diller Scofido + Renfro)

following your curiosity.

With no set pathway or journey through the collection, we were free to roam at will. The Storehouse experience is about browsing, serendipitously discovering objects and making connections between them. To provide some degree of structure to the narratives that can add context and interest to the collection’s vast depth there are over 100 mini-display vitrines. These micro storytelling moments, literally ‘hacked’ into the visible ends of the racking structures offer a cross-section of the V&A collection. Standing in the central core you are given a strong sense of the breadth of material represented in the collection through these small snapshots.

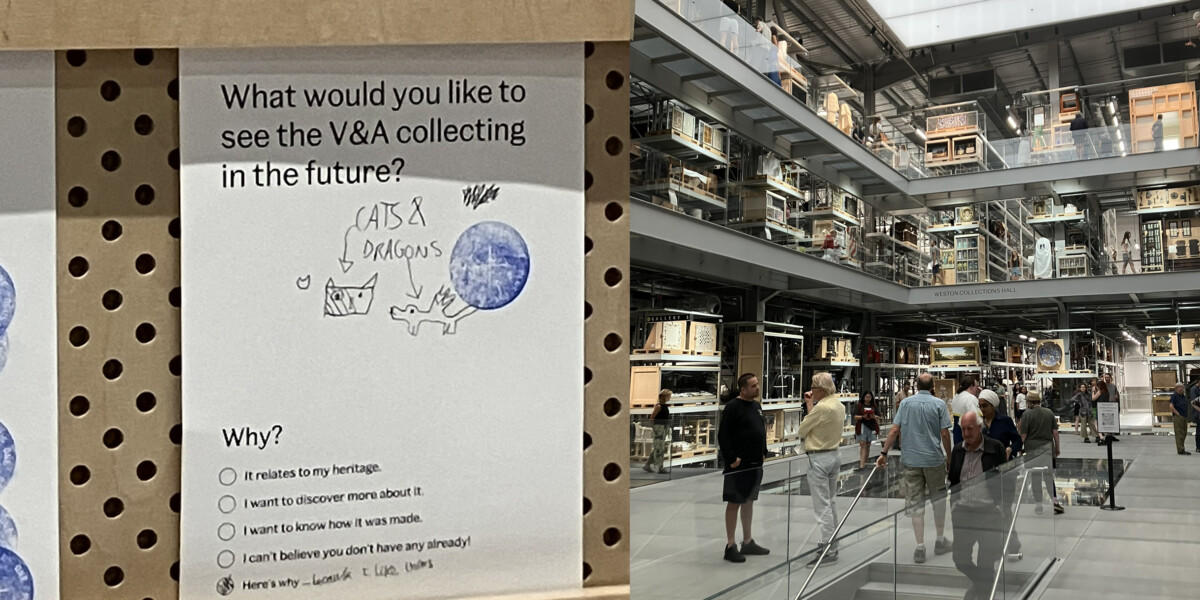

With the sheer volume of cultural artefacts on display, gaining valuable insight still requires some direction and explanation through curation. Feature displays prompt visitors to question their thoughts on the displays by posing questions alongside collected and often juxtaposed items- “What should we do with looted objects?” or “Do you collect any memorabilia or keepsakes?”.

This conversational tone, and questioning prompts as you discover the collection reflect a wonderful truth at the heart of the Storehouse and its purpose: it’s all about people. Everything here- architecture, activity, curation- moves toward one goal: making connections.

The spirit of openness that affected me more as our visit went on, shows up in unexpected ways. The details such as the display texts aren’t anonymous, the notes and explanations are credited, giving a voice to the curators and museum staff who are typically invisible but here are breathing life into these stories with a language and approach that feels immediately human. It feels less like being lectured to, and more like being invited into a discussion.

The objects we discover become conversation starters, helping us make sense of where we’ve been and what may be next. The V&A isn’t shying away from difficult conversations either. By working alongside varied communities locally and globally, the museum is opening its spaces for discussions around colonialism, social mobility, class, and who has the right to decide what is culturally important.

[Image Credit: Hufton + Crow]

but is it art?

The V&A’s mission is to not just collect the treasures of the past, but the “artefacts of the future”- a living cross-section of contemporary art and material culture. The purpose of the collection is clear- to show that heritage is not a relic we stumble upon fully formed; it is something we create every day. That’s why the V&A has always been my favourite museum. And in the Storehouse, one piece moved me more deeply than anything I expected: a towering 9-metre section of the now-demolished Robin Hood Gardens housing estate.

Designed in the 1960s by Alison and Peter Smithson as a bold, utopian dream for social housing meant to breathe new life into the East End. But after decades of neglect and controversy the estate was demolished in 2017. The V&A acquired and preserved the section of the façade as an important example of brutalist architectural heritage, worth preserving; but this is more than an act of salvage- it’s a statement.

The façade is a fragment of modern cultural heritage that doesn’t fit within traditional ‘museum-worthy’ tropes. It is rough-edged, controversial, and deeply human. The concrete slabs are a monument to the lives lived within them and to the biases of class and taste that so often decide what we keep and what we discard- what is deemed of value.

This fragment of social history challenges us to consider the Smithsons’ ambitious vision for society, and the role architecture plays in shaping our cities physical and social structures. Seen alongside everyday details salvaged from the estate- letterboxes, door knockers, the small things of daily life- the installation becomes even more moving. It’s not just a piece of concrete; it’s a reminder that heritage lives in the ordinary as much as in the extraordinary. It asks us to reflect on home, memory, loss, and how we want to live in the future.

[Image Credit: Joe Gilbert + VAM]

A view from the studio

The V&A East Storehouse was an incredibly exciting, innovative, and surprisingly moving experience that made me fall in love with museums all over again.